The Curious Election

A recipe how to make your town (in)famous

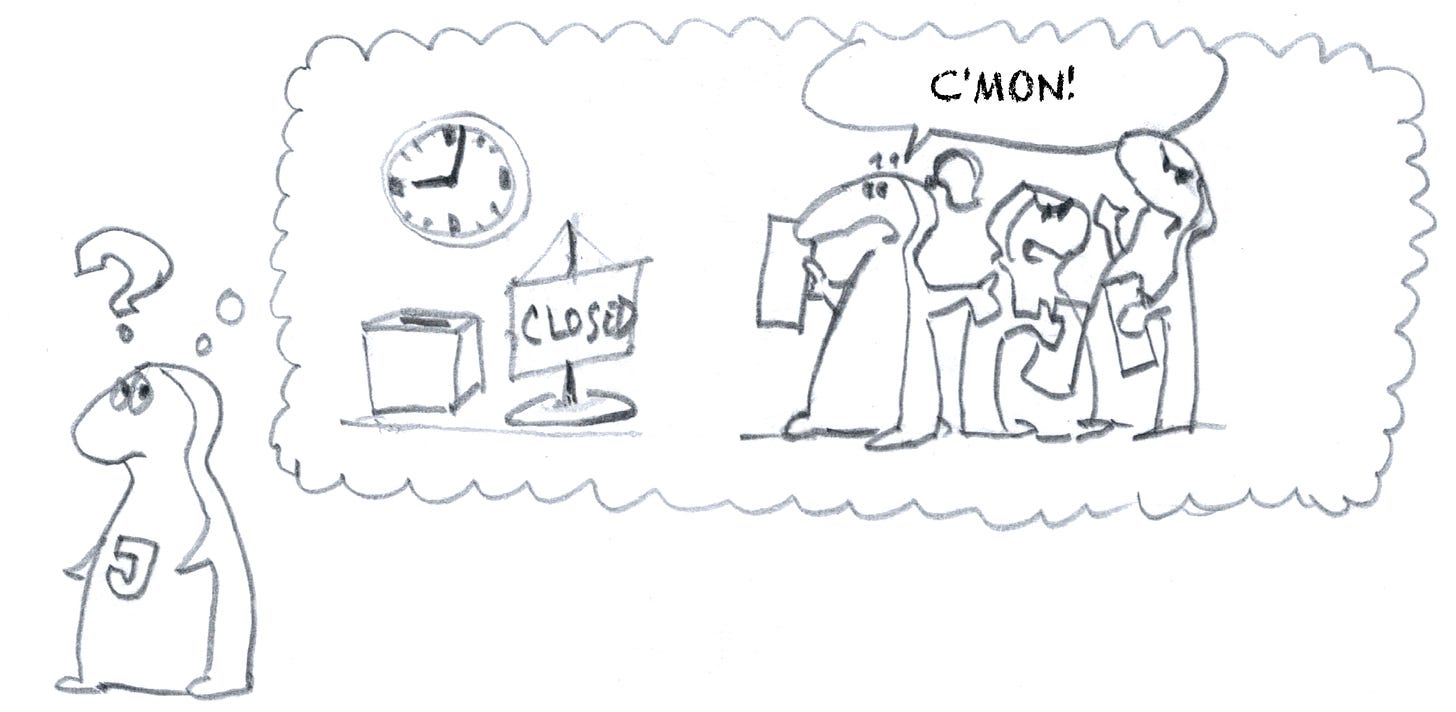

Do you like fairy tales? As a child I used to particularly enjoy tales that had interesting twists in them and made me think (my favorite one about “A Boy Who Stopped Time” by Olga Scheinpflugová). Well, it is time now for me to write one such fairy tale for you and I promise it has twists that will make you think. It is a tale of a curious election based on a real story, albeit with character “dramatization.” Please stay with me, just dusting off my old typewriter.

Once upon a time, in a kingdom far away, a curious election was held. The king called upon six candidates to run for his city council.

The king also had a wizard (profession today known as “lobbyist”). Based on the wizard’s advice the king—without much thinking—decided to add:

The candidates, oblivious to what IRV meant, worked happily and campaigned hard

and, as a result, 1803 voters cast their votes.

The king purchased a very expensive IRV counting machine because the old one could not count the new fancy ballots.

According to the machine, candidate Jason was elected winner and that put smile on his face. Candidate Luke (one of the five losers) was unhappy,

more unhappy than the remaining four, for a good reason though: After counting all preferences, Luke learned he defeated all five opponents head-to-head. The following table gives detail. Luke (LW) defeated the IRV winner Jason (JT) by 1191-to-835 pairwise preferential votes. He similarly defeated all the other candidates, by a solid margin:

Yet he lost. A haunted election you may ask? Well. In election sciences, Luke is referred to as “Condorcet Winner” and situation like this is called “Condorcet Failure.” A preferential counting method that fails to elect a Condorcet winner is considered deficient. But, there is more to our tale: Had three voters who voted against Jason (the winner) not showed up at the polls (say they were late), surprisingly, Jason would have lost.

A wizard’s curse? There's more. Had three voters changed their vote in favor of Jason (the winner), Jason would have lost (say, three voters reconsidered and up-voted Jason based on latest gossip while waiting in poll line)

Is there an end? There is more, I'm afraid . Had 765 additional voters showed up voting against Luke (a loser), Luke would have won, and Jason would be a loser!

If your children are into puzzle-like bedtime stories, this one is undoubtedly a keeper. So, who should have been the winner? What if more people voted for me - would I still be the winner? Should I have asked more people to come and vote against me - then I could have won? Your children—if not fallen asleep—would probably give us an acknowledging nod: “That wizard was a meanie.”

Back to reality: Replace penguins (yes, they are penguins) with humans. The name of the town where this all happened is Moab, Utah, and the election year was 2021. But how can such non-sense be real? Let me explain.

How did Utah get IRV?

On March 19, 2018, Utah Bill HB00351 was signed by then-Governor Gary Herbert launching a “Municipal Alternate Voting Methods Pilot Project.” The project allows Utah municipalities to conduct preferential “Ranked-Choice Voting (RCV)” elections uniquely tied to a controversial counting method called Instant Runoff Voting (IRV). A voter may choose to rank all or a subset of the candidates in a race. Tied preferences are forbidden. The IRV algorithm works in multiple rounds as follows: in each round, only the top candidates of each ballot are tallied. If there is no majority winner, the candidate topping the fewest ballots gets eliminated and his/her votes automatically transfer to the next-ranked candidate on each ballot. The eliminations continue until one of the candidates achieves majority.

Pitching IRV to Utah municipalities has revolved around (1) a financial argument (IRV makes primaries unnecessary), and (2) supposed electoral benefits (e.g., avoiding the “spoiler effect”, producing a “majority” winner, encouraging “amicable” campaigns). These claims can be found all over pro-IRV advocacy websites even though most can be rebutted and/or shown profoundly flawed. The largest proponent of IRV in the USA is FairVote.org (an organization funded, among others, by the Soros family’s Open Society Foundation). We are going to dedicate a separate article to deconstructing the main pro-IRV claims. But for now, let’s just take a look at what actual data tell us: a study that was done with my co-author Warren D. Smith based on ranking data from Utah County in 2021.

In our study, we assess how IRV worked in Utah not based on voter surveys (that measure voter satisfaction - only a half of the IRV story) but based on hard data: we evaluated the rankings, created software to detect anomalies, paradoxes and pathologies. Here are our findings summarized in two points.

Finding 1: Extraordinary Voter Disenfranchisement

Unlike in a survey where a voter may say “I loved Ranked Choice Voting!” we look away from how they “feel” and into how they actually handle/cast their ballots. The finding is not pretty. While a typical plurality election is associated with a small percent-point fraction of discarded ballots (e.g., due to being empty), the RCV ballots evidently caused a major game change. Voters were asked to rank up to 9 candidates, without making a mistake: no gaps, no double rankings. A staggeringly high percentage of ballot waste and ballot “impurity” ensued. The following table summarizes basic statistics for the 17 races across Utah County:

The column “Discarded Ballots” lists numbers and percentages of ballots that were thrown out because voters made mistakes of the likes described in this post. It is up to you to choose a pain threshold: is 5% ballot loss enough to get upset? If so, that threshold is exceeded in seven races! We also see cases like Genola where about a third of voters had no voice in their Council race (Seat 2) due to ballot discardment. Our report details on how this happens.

Finding 2: Serious Pathologies (Illogical Election Outcomes)

Let me be clear, our introductory fairy tale reflects a real story. IRV in Moab has delivered several major paradoxes: (1) given Jason Taylor being a declared winner, had there been (at least) 3 voters who switched their vote in favor of Jason, they would have made him to a loser. More outrageous are so-called “Participation Failure” paradoxes where (2) “at least 3 voters who voted against Jason not made it to the polls” Jason would lose, or (3) “had at least 765 additional voters who voted against the loser Luke Wojciechowski showed up at the polls” Luke would have won. I hope your head is spinning, as it should - it means you are fond of rational thought. Imagine a plurality election where someone wins with 100 votes, but, all else being same, loses with 103 votes!

The following table from our report summarizes phenomena that occurred in the 2021 Utah IRV elections:

We refer the curious reader to Section 3.5 of our report for detailed explanation of the individual metrics. But I will pick couple of additional observations:

IRV differed from plain plurality outcome in only 1 out of 16 races. It seems Utah voters pay a hefty price filling out complex IRV ballots and losing their voice for just a 1/16 difference compared to regular elections.

IRV advocates sell IRV as a method guaranteeing majority winners and avoiding the “spoiler effect.” It is repeated by almost every IRV site and every official who heard the lobbyist presentation (I don’t blame them - it does sound so good). In reality, however, no majority was achieved in 3 out of 16 races (see column “Failed Majority”), and in 1 (Moab) there was a spoiler candidate, Josie Kovach (see column “Loser Dropout”), all clearly contradicting the IRV’s #1 claim(s).

What now?

With wider adoption of IRV we will continue seeing issues like the above (most recently seen in the special election in Alaska). And it is only a matter of time when voters will wake up and get upset about how their votes get counted. Poundstone’s book “Gaming the Vote” describes the long history of vote counting, weighing pros and cons of the numerous methods. It is surprising to me that we continue implementing one of the most “broken” among them. It is also clear, that in states with pilot programs like in Utah tying IRV to RCV, a discussion has to be re-started. Voters have questions: is IRV the only viable way to count preferential votes? If not, what alternatives are there and why were they not considered? By the way, my co-author, Warren D. Smith, has an answer: adopt “Range Voting” (aka Score Voting) and you shall never see the “More Votes is Less” paradox and many others. I couldn’t agree more. But it is not about me, it is about an educated decision-making process in the legislature and about voters deserving exactly that. That process also includes proper legislation to guarantee election data release for independent analysis by researchers. Ask me what I was told when requesting data from the Salt Lake County Clerk!

Open Research

We are independent researchers who are interested in collaboration and data sharing. We believe openness and transparency are essential in keeping the technical debate honest and (as much as possible) free of politics. Reach out to us if you are interested in obtaining the Utah and Alaska data.

More Info

Range Voting - a treasure chest of in-depth information about ranked choice voting methods

Post on Genola’s painful IRV election

Full technical report on the 2021 Utah IRV Elections

Video presentation explaining the concepts and problems with IRV in Utah

Podcast “Straight Talk with Kim and Carolyn” discussing the Utah IRV topic

Douglass Frank/Mike Lindell developing some kind of drone-style signal detector that would force transparency. I’d rather see Shasta County replicated statewide. Last night, asked a state level GOP insider where she stands. “... uh, gotta go, bye.” (To be fair, she said Shasta only happened because it’s so small... tHen she had to go)

We’re in LosAngeles where county machines are replacing all former ink-a-vote (& other) methods. Beyond skeptical. Incensed.